There is a problem with how we deal with issues. Both personally and societally. When people make mistakes, we merely focus on holding them responsible. When errors occur, we treat them as exceptions. However, this neither prevents future similar mistakes, nor is it a fair judgement of the individual. Future similar mistakes won’t be prevented if systematic changes are not implemented. In other words, if we do not make it less likely for these mistakes to happen. Further, fairness towards the individual is deprived since the mistake of the individual cannot occur if the required environment and tools are not available to them. The person makes the mistake through the physical and mental tools they acquire and develop through time but also within the space that welcomes it at the right moment. This reality is ignored by the individual-centric assessment of the mistake. Therefore, by holding the individual responsible, for the mistake, we assume they acted alone and in a vacuum. We treat the individual as separate from others, as an exception. But by ignoring patterns of mistakes made by numerous other people, we also treat every data point as an outlier. While individual responsibility does remain to a certain extent, it does not cover all the factors that contribute to the mistake or error. What makes the absurdity of this approach ever clearer is how globalized and connected modern cultures have made almost everybody. In modern societies, systems are also complex; do we appreciate the implications of this?

Our educational and cultural institutions shape our actions and thoughts in specific ways. We adopt by default certain perspectives and acculturation occurs and is reinforced daily. This is present in all stages and domains of our modern life. In our professions, we are trained to do things a certain way and are imposed directives and incentives that structure our process and impact the quality of our work. These forces habituate us to view individuals as separate beings, detached from their environment. Recognizing this can lead us to appreciate the context from which mistakes and errors arise. How much of an error is the result of individual factors, and how much is from environmental factors? But since we don’t think this way, errors continue. What could have been solved becomes a chronic problem as we manage and prolong it. Why do we fail to make this assessment? Because we lack awareness. We are each aware of ourselves and of the surrounding environment, but we separate the two as if they barely affect each other.

Awareness is often divided into self-awareness and environmental awareness. The narrative follows the pattern of the me who is affected by the surrounding world. It is in opposition to this me, that springs forth the notion of the other. This is precisely because the other is defined as “what is not me”. With little scrutiny, then, it becomes apparent that without the notion of “me”, there can be no “other”. That is unless we recognize that this duality, we entertain is not two separate notions but two sides of the same coin. Me and Other are both essential to one another and their interdependence is a core feature of what I call Ecological Awareness. Simply put, Ecological awareness is a holistic recognition of reality; one which appreciates the interconnectedness of the figure and the background.

“In the Gestalt theory of perception this is known as the figure/ground relationship. This theory asserts, in brief, that no figure is ever perceived except in relation to a background.”

Alan Watts, The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are

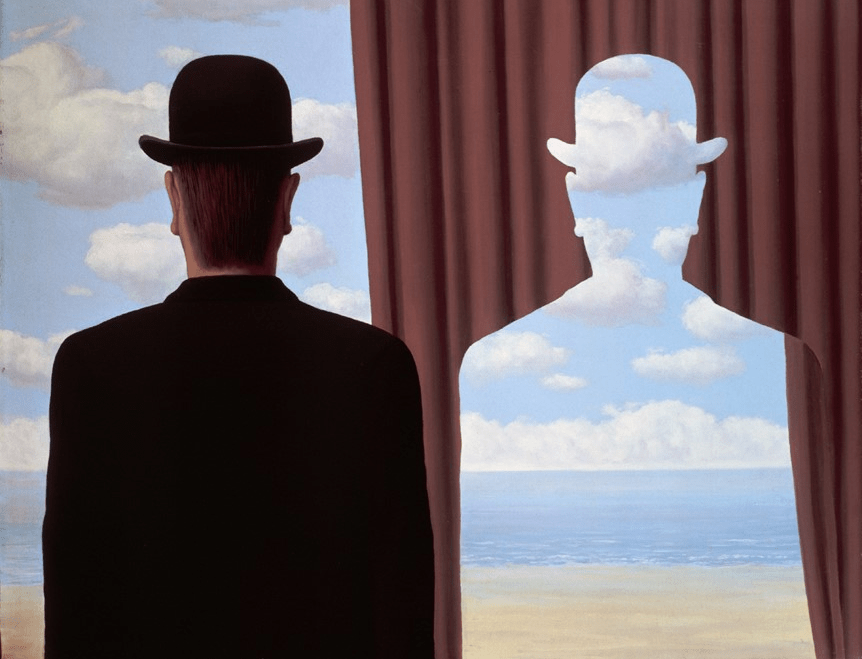

This is the kind of awareness that results in prolific musicians, writers, and speakers balancing out their musical notes and words with silence. They appreciate silence and value it because they do not see it as merely the interval between the sound. The silence, they understand, collaborates with the sound. The music then flows with beauty as the note and the silence harmonize. The same can be said of prolific writers. The weight of their words is felt through length. One sentence long, another short. And the richness of the text is felt in the transitions between one sentence to another. The artist who paints might be one of the very few kinds of professionals who by the virtue of their training appreciates this. Painters are trained to begin with the layers of background and to continue adding onto the canvas with each detail. The figure, for them, is placed into the background, where they ‘match’ with their surrounding and give the totality of the piece a sort of unison. This generally refers to the concept of figure/ground which is about perception itself. Amongst artists who have experimented with this very idea, rather than merely employing it, we can name surrealist painter René François Ghislain Magritte. Some of his most famouse paintings are La Trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe), 1929 and La Décalcomanie, 1966 (seen above).

Thus being aware of the interconnectedness between figure and background allows us to look at systems along with the individuals within them. We begin to appreciate the magnitude of influences on people and all the situations they are forced into where they are naturally inclined to make mistakes. For instance, we can look at events of police brutality and recognize the structure and system that is enabling them. This realization also saves us from the discourses of good people vs bad people. We are less likely to put all the blame on a single person for tragedies and large-scale horrors when we know that they could not have acted alone. But maybe the most beneficial result will be a practice in accurate living. We will see things more clearly but also judge and talk about them more accurately. No longer satisfied with vague labels of “good” or “bad”, we will talk of the factors that aided or hindered the progress of an error or mistake. We will look with more attention and take our time to make sure we can say what exactly it is that “feels wrong” about the situation. in bad environments will make mistakes. Not just our day to day lives, but also our systems and institutions would benefit from this. Unfounded and erroneous incentives and policies that would increase the rates of conflicts would diminish. Solutions would actually solve our problems, rather than postponing them until they are too frequent or extreme to ignore.

Mistakes and errors happen because of flaws in our reasoning and systems. They are not to be judged as good or bad, but instead understood and learned from. With a proper attitude, we can have less errors and be fairer in our treatment of people. All of this is possible, nothing is out of reach, and it starts with us and our perspectives.